This Chicago science teacher tackled chemistry and racism in her virtual lab

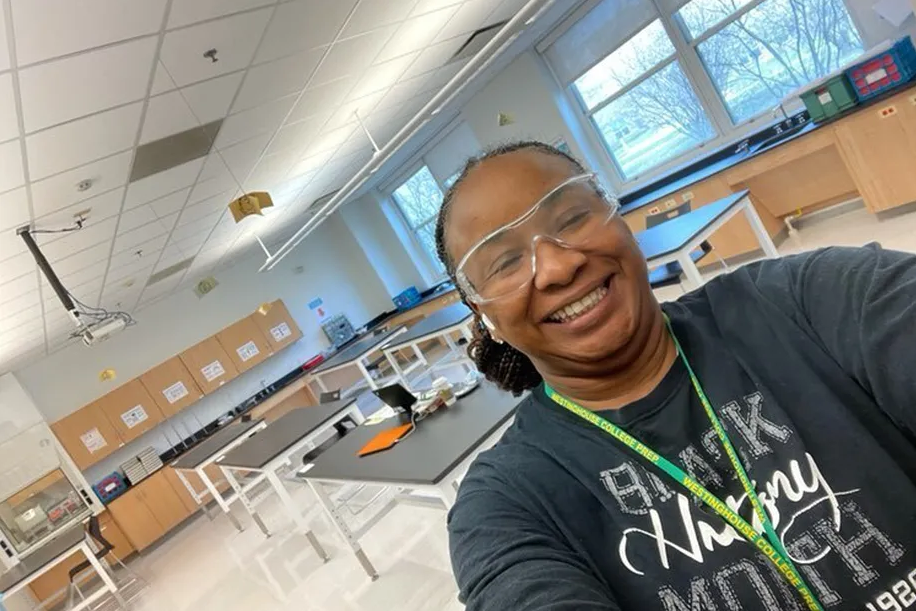

June 11, 2021For Chicago chemistry teacher Nina Hike, a year of unprecedented upheaval was especially eventful.

Last spring, she was featured in a Chalkbeat and Chicago Tribune collaboration that chronicled Curie High School’s foray into remote learning, highlighting Hike’s dedication to her craft and her humility. Then in the fall, Hike returned to the West Side where she grew up to teach at the selective enrollment Westinghouse College Prep, starting out another virtual school year at a new school — a daunting transition that sometimes brought her to tears. To top it off, Hike recently learned she is a state finalist for the Presidential Award for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching, the country’s highest honor for math and science educators.

She spoke with Chalkbeat about making chemistry more relevant to her sophomores’ lives, empowering young people to use their voices, using her platform to tackle racism, and learning to surrender more control over learning to her students.

What challenges do you face teaching science during this year?

This was the most challenging year of my teaching career, more than even my first year of teaching. I don’t ever cry, but I cried this year. At times, my internet wasn’t working. My students are in our virtual class, and I’m not in there. I know that I could teach better if I could just write on the board — do what I normally do. That set off a lot of sadness because I’ve never not been able to do my job.

There was also the adjustment to simultaneous teaching. You have the students who are in person, and then the kids online, so you feel bad if you aren’t managing your time with those two groups. I’m trying to make sure that I give everybody the attention they need, even though it’s divided.

How did you adapt your chemistry lessons to the virtual classroom?

Connecting the chemistry to societal situations has really worked for me. We looked at who decided to criminalize marijuana. And why is it all of a sudden OK to sell it and make profits off of it while a lot of Black people are in jail for that? We also looked at how drug tests work and how accurate they are — the whole science of faulty tests and false positives. If students or their families take a drug test for a job and get a false positive because they take a medication that has a similar molar mass to marijuana or other drugs, they can contest the results.

I try to show students how science is used throughout society to make it relevant for them. We spoke about the demolition of the Crawford Power Plant plant in Little Village and about Chicago having lead water pipes as examples of environmental racism. It’s about their community, and issues they can identify in their community, so that they learn how to fight back.

I know last spring, you took time to talk with students about George Floyd’s murder and its aftermath. Have you been taking a step back from chemistry this school year because you felt students might need to talk through something in the news?

At the beginning of the school year, we go over the different types of racism: internalized, interpersonal, institutional and systemic racism. We talk about microaggressions. We develop class expectations so that students can hold me and each other accountable.

Later, we spoke about Breonna Taylor and reflected on what happened to her. I don’t like it when people turn these events into one-time tragic events, and don’t really connect them to anything else. Instead, I told students, “We’re going to talk about systemic racism because this is all systemic racism. The system needs to be changed so police can’t do these no-knock warrants.”

I told students that I have to bring my full self into the classroom. I have to bring the science person, the mother, the sister, the daughter, and the Black woman. I have to bring all of those identities into the classroom with me. And I want students to talk from their own perspectives, and not be afraid to challenge what’s happening during class.

I also became a co-sponsor of the Black Student Union. We really had a successful year having open conversations and a space for students to talk about racial issues within their schooling. During Black History Month, students were leading sessions about Black identity, Black intelligence, Black finances, Black beauty and code-switching. To see students do the research, and then lead a group of 100 people in a conversation about it was phenomenal.

Do you hope that the pandemic, with all of its disruption, will bring some longer-term changes to public education? What changes are you hoping to see?

I’m hoping to see the education system really tackle racism. Some states are passing laws against talking about racism. I can’t even believe it. My dissertation is about critical race theory.

CPS pushed out the “Say Their Names” Toolkit (resources to guide conversations about racism). Schools can’t just opt out of discussing this. I hope we still keep going with that.

The responsibility to discuss these issues should not fall on Black, indigenous and other teachers of color. It’s our collective responsibility. It’s hard, and it’s taxing to be that person who speaks for everyone else. We need more authentic allies who are really trying to make sure that their curriculum is culturally relevant and anti-racist. As teachers, we need to do a lot of self-reflecting and think about ways that we’ve internalized racism. It’s time to really look at what we are doing and give students some voice.

How are you working to give your students more voice and agency in this moment?

I was happy this year because some of my students really questioned, “Where do these rules come from? Who did this?” I told them that scientists get together, and they provide evidence, and they decide what’s going to be relevant. Pluto is not even a planet anymore because a group of scientists got together and provided the evidence to sway the scientific community. In the future, you could be a scientist, and you can make some of these rules. But we also use science in ways that aren’t beneficial. So we have to be able to interrogate science.

I’m hoping teachers will begin to be more like facilitators of learning. We have to let go of always being in charge. During remote learning, we teachers lost control. We had no control. We were sitting there hoping students open their mouths and respond to our questions in the online class. But this was always supposed to be about shared decision-making in classrooms where students are able to make more choices — real choices. That is what I’m hoping for.

At the tail end of such a trying school year, what was it like to learn you are a state finalist for the Presidential Award?

It was an awesome feeling. I initially thought the application would be a lot of work, a lot of different steps. But it helped me see all that I have done over my 25 years of teaching. I thought of all my students over the years, and of seeing many of them be successful in their careers. A lot of them are science people, organizers, veterinarians. They’re in law school.

It was a good reminder of who I am as a teacher because remote teaching was challenging due to the limited interaction with students. Revisiting all the exciting things that I have done gave me the energy to make it through this school year. It was definitely uplifting. Still, I never would have thought that I would be a finalist. I was very excited.

This article was originally posted on This Chicago science teacher tackled chemistry and racism in her virtual lab